A career that quickly led him to collaborate with renowned studios on increasingly ambitious films such as Black Panther, Patrouille, and the Ms Marvel and Skylanders Academy series.

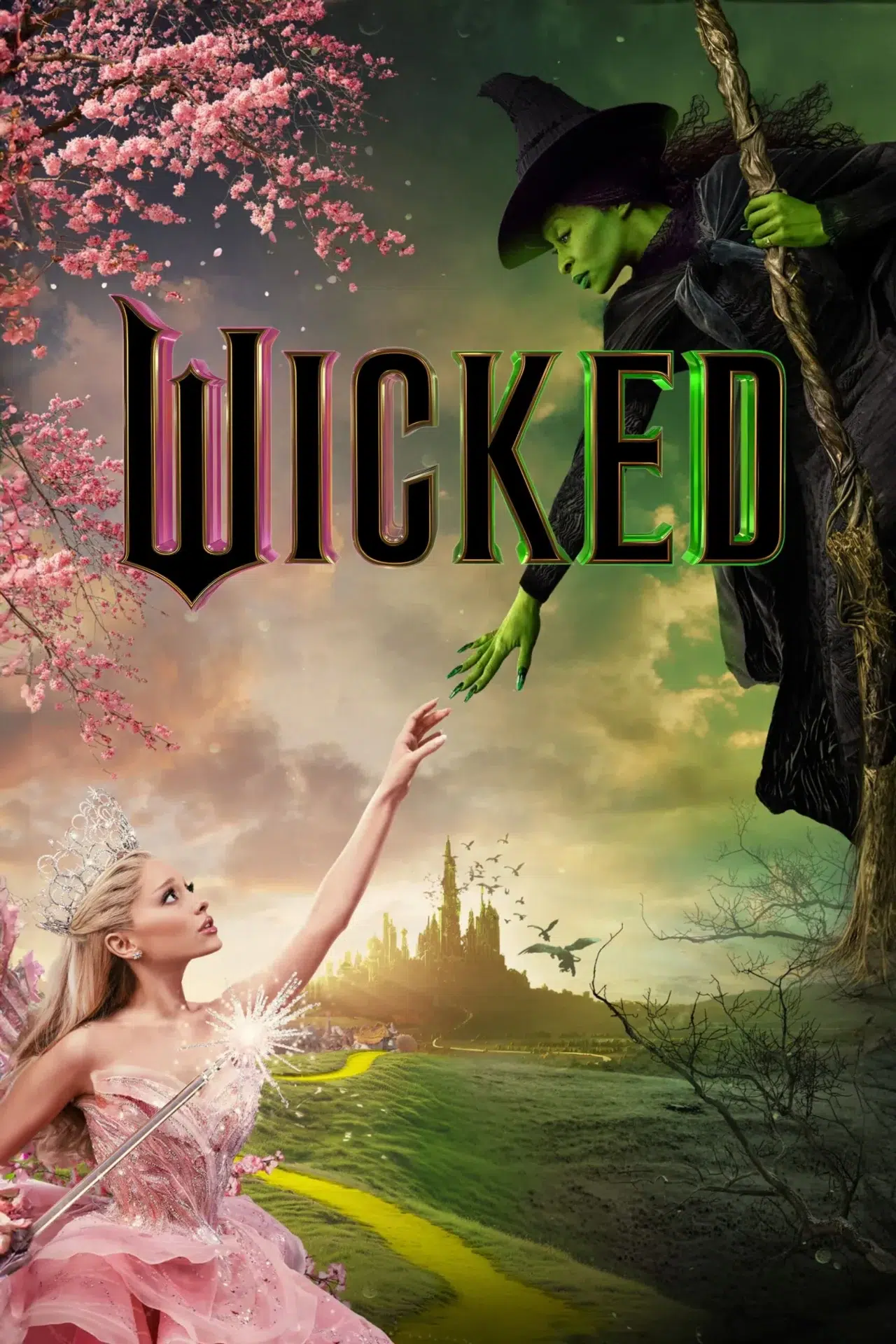

This year, Wilfried Lhomme‘s name can be found in the credits of two of the biggest blockbusters of the year, having collaborated (with Framestore) on F1, released this summer, and on the sequel to Wicked , now in cinemas.

How do you become a crowd artist, what are the challenges of the job, and how do you envisage a career in this field?

These are just some of the questions we asked the former student, now well established in the industry.

Can you tell us about your career path after leaving school?

First of all, I’d like to make it clear that I didn’t finish my studies at ESMA. I did my first two years there, and then moved on to the Pivaut school. That said, those two years enabled me to build up the basis of my skills base, a generalist apprenticeship that has helped me a lot in the years to come.

When I left school, I quickly realised that I needed to do work placements to get into the studios quickly, and I sent a lot of emails to that end. Onyx Films was the first to reply, and I started my career on the series Drôles de petites bêtes, as an animator. This was followed by a placement at La Station Animation, still working on the same series, and then I was lucky enough to do a placement in Montreal at On Animation, which was producing the Playmobil film at the time.

After Montreal, you returned to France to work for TeamTO?

The truth is that I could have stayed in Canada, but my visa expired and I didn’t get the renewal in time. So I went back to France, and that’s when I was hired by TeamTO to work on Skylanders Academy and then Pyjamasques. After seven months working together on these two projects, TeamTO decided to stop the collaboration, telling me that my level of animation wasn’t good enough.

As I hadn’t finished my training at ESMA, I took a year off to hone my skills and work on my animation, and I went to Annecy. That’s where I met the BUF Compagnie recruiters, who offered me a job as an animator in Montreal. I haven’t been back since.

How did you become a Crowd Artist?

It was during the Covid period that this transition took place. I’d been on a break because of the pandemic, and my PVT was about to expire. A friend had left BUF and returned to Mikros, in crowd animation, and she told me that Mikros was looking for someone with animation skills to join their department. I didn’t know the field at all, but I ‘fell in love’, as we say here in Quebec.

Since then you’ve worked on a number of projects, the latest being Wicked: For Good. How did that production go?

For the crowd, we mainly use two tools: Golaem, a Maya plugin, and Houdini. Before joining Framestore, I had mainly worked on Golaem (notably for Miraculous, at Mikros), with only one experience on Houdini during my collaboration with Digital Domain on Marvel projects. But despite all that, I was quickly able to make my mark on Houdini en crowd, through F1 , on which I worked for over a year.

On Wicked, things went really well. I mainly did ‘shots’.

In TD, we generally do either a shot or a setup, for a very specific sequence where we needed to reinforce the animal crowd animation.

You can see it in the trailer, and I took care of the animals in the background, while the ‘main animation’ team was responsible for the creatures in the foreground.

What are the special features of crowd animation?

In this project, the setup was very well executed, which helped us a lot and even enabled me to finish these shots ahead of schedule. Crowd control is an area where it takes a lot of time to set up the set-ups. But once they’re set up, you can diversify them on a huge number of things, and so copy and paste our setup to adjust it to each of the shots.

It’s a bit technical, but it will make the work go a lot more smoothly, and even if you’re behind on the first shots, you can easily catch up on the following ones and balance out the whole pipeline.

And how did this work out in practice?

Here, I had as many land animals as air animals to integrate, so there were two types of setup.

In Montreal, there were two of us working on the film, with a colleague with a more technical profile based in London.

Generally speaking, the crowd teams are quite small, but we interact with a large number of positions, whether rigging, animation or texturing, depending on the project.

Here, we exchanged information with the fur artists, but also with the riggers to recover the birds’ rigs and so on. The power of Houdini is that the software offers a huge range of data transfer options. We recover the rig used by the animators, we lighten it according to the distance from the camera, and we also recover the animation cycles that interest us.

For Wicked, it was a really special case because there are a lot of different animals in this shot, each with their own specific action that had to be multiplied by the number of animals on screen.

In your job, you are in constant communication with many people. To what extent is this ability to communicate more important than technical skills?

It’s extremely important. In crowds, we have technical knowledge that is closer to rigging, or seeing how an animation works, but not all crowd artists have the same background.

What’s going to be very important is knowing who to turn to in order to adapt the assets to our specific needs. So we need to be able to communicate with the right people.

As crowd artists, we often communicate with the supervisors, whether it’s the CG supervisor, the animation supervisor or others, who then delegate to their teams, which allows us to really rub shoulders with those who run the project. It’s like ping pong between us and the other departments, and it’s very rewarding.

You mentioned F1, which you worked on just before this project. What struck you about that production?

I worked on two large circuit sequences, with a fairly static crowd (made up of spectators). But even so, we were in constant contact with the modelling teams when we needed part of the circuit’s grandstands, or if there were chairs or tables that weren’t at the right height.

We also had a lot of discussions with the lighting department, to make sure the colours were right. In the end, because we talk to all the departments, we get a fairly global view of the project and can quickly direct people to the right people if certain aspects of the film need to be reworked.

Each project brings new challenges and new experiences. What has Wicked taught you as a crowd artist?

It was the first time I’d worked with animals, but also the first time I’d worked with Houdini 25, which meant some major technical changes.

These developments (in two words, moving from a system of particles to a system of motion paths) offer new freedoms but also new constraints, and we need to be able to adapt.

With this load of animals, we had to avoid the different body types interfering with each other, and that taught me a lot. Similarly, the flight animations and the different tempos we had to integrate into them posed a number of challenges.

Another interesting aspect of the film, even though I didn’t work on it directly, is that of a crowd generated from a photoscan. A small group of costumed actors were used as the basis for generating this crowd. Their reactions were filmed by a multitude of cameras, and this made it possible to render a realistic crowd through a system of points, something I’d never seen before.

What would you like to share about your job today?

It’s a little-known but very interesting profession. I’ve started giving courses in various schools, and the students are generally very curious. To sum up, I’d say it’s a very generalist job, but more on the technical side than the artistic. Having code skills can help with certain aspects of Houdini and Golaem, which use simplified codes but whose logic remains similar.

The advantage is that it’s a job you see on screen every day, even though many people in the industry are unaware of its existence. To use crowd artists, you need a relatively large budget, so it’s often the big studios that call on our profiles.

In fact, the crowd artist can have a wide variety of situations, with sequences like the circuit I mentioned earlier, battles, or even street scenes, but without him, the scene can seem very empty. So there’s a very satisfying aspect to seeing his work on screen.

But don’t forget to be humble too, because your work isn’t necessarily the star of the show.

And any advice for those who want to go down this road?

Whatever the project, whatever the world you’re working in, what seems important to me is to remain curious, to always try to renew yourself and try new things. Don’t hesitate to specialise as soon as you start studying, and concentrate on the aspect of the job that you love. I’ve succeeded, so anyone can succeed.

Now Senior Crowd Artist for DNEG, Wilfried Lhomme is delighted with this new stage in his professional career. DNEG’s projects, including the Bollywood blockbuster Ramayana (a half-historical, half-mythological fresco that promises to be a very large-scale project) represent new challenges for him, and an opportunity to explore this captivating profession even further.